unmapped: rethinking ADHD neurology

This post comes in whatever flavour your brain wants today:

a visual zine or a plain-text/written version.

Want a copy of this zine?

Download the PDF and feel free to print or share it with others.

Please credit Gillian Hestad (Divergent North) as the writer.

Suggested credit line: “© Gillian Hestad, Divergent North — used with permission.

UNMAPPED — RETHINKING ADHD NEUROLOGY (Blog Edition)

SYNAPSE SYNOPSIS V. 3 - Fall 2025

written by Gill Hestad / DivergentNorth.ca

Dear Reader,

This zine is about how ADHD brains are wired differently:

tuned to salience, driven by meaning, alive to what feels urgent and real.

ADHD isn’t disorder.

It’s a natural and valid variation of human neurology.

Across these pages you’ll see images of the brain layered with research — re-examined not as deficits, but as variations.

Let’s explore it.

REDUCED SENSORY GATING (P50 → P300 CASCADE)

Micoulaud-Franchi, J. A., et al. (2016). Sensory gating capacity and attentional function in adults with ADHD. Psychiatry Research, 240, 209–214.

Science Says: Adults with ADHD show reduced early sensory gating, letting in more sensory information, which in turn reduces P300 responses downstream.

In Plain English: More noise slips through the filters. That means every sound, flicker, or tap can demand attention.

*This is a brain tuned to notice more. It can feel overwhelming in busy environments, but it also supports creativity, curiosity, and noticing patterns others miss... turning distraction into discovery.

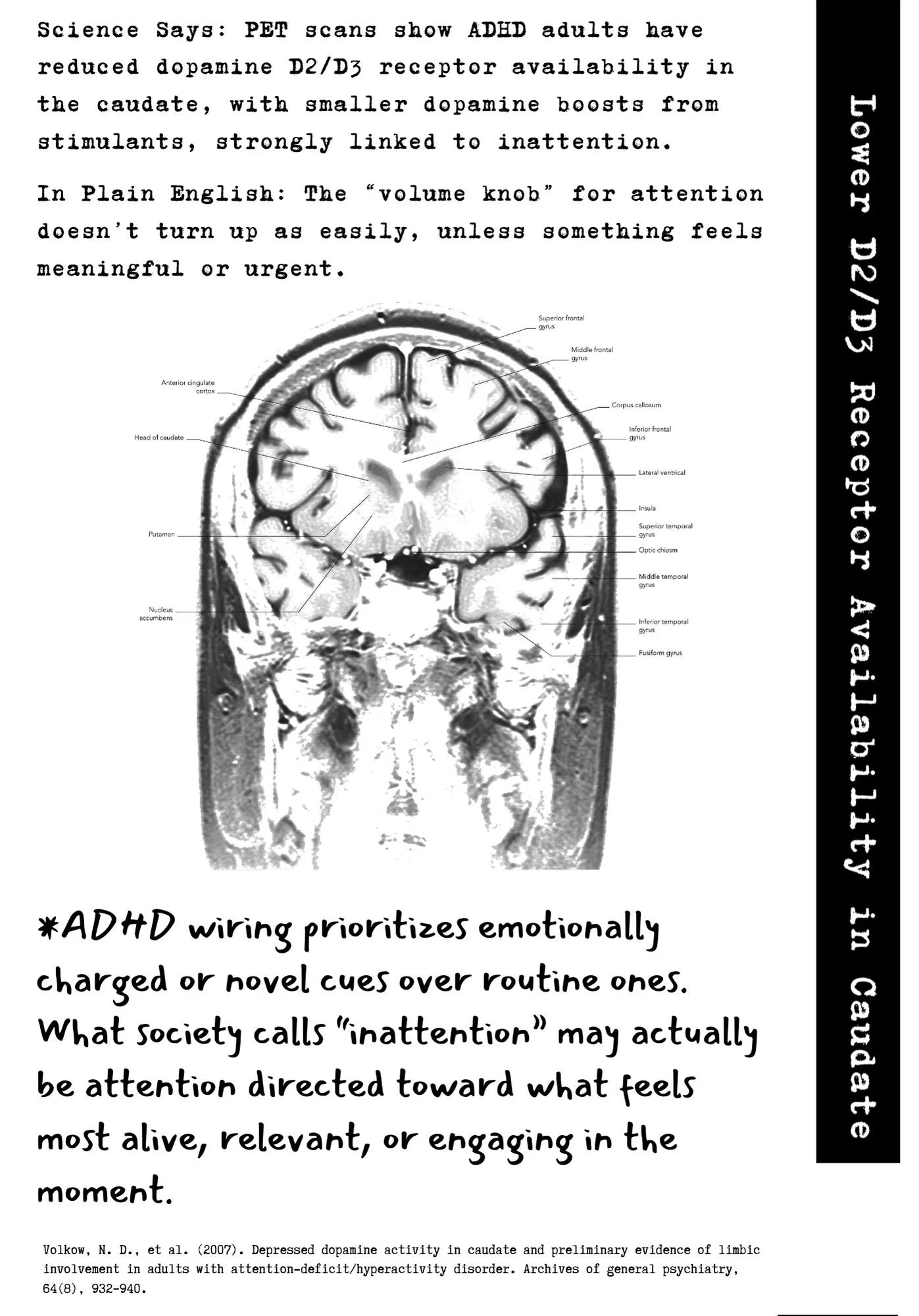

LOWER D2/D3 RECEPTOR AVAILABILITY IN CAUDATE

Volkow, N. D., et al. (2007). Depressed dopamine activity in caudate and preliminary evidence of limbic involvement in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 64(8), 932–940.

Science Says: PET scans show ADHD adults have reduced dopamine D2/D3 receptor availability in the caudate, with smaller dopamine boosts from stimulants, strongly linked to inattention.

In Plain English: The “volume knob” for attention doesn’t turn up as easily, unless something feels meaningful or urgent.

*ADHD wiring prioritizes emotionally charged or novel cues over routine ones. What society calls “inattention” may actually be attention directed toward what feels most alive, relevant, or engaging in the moment.

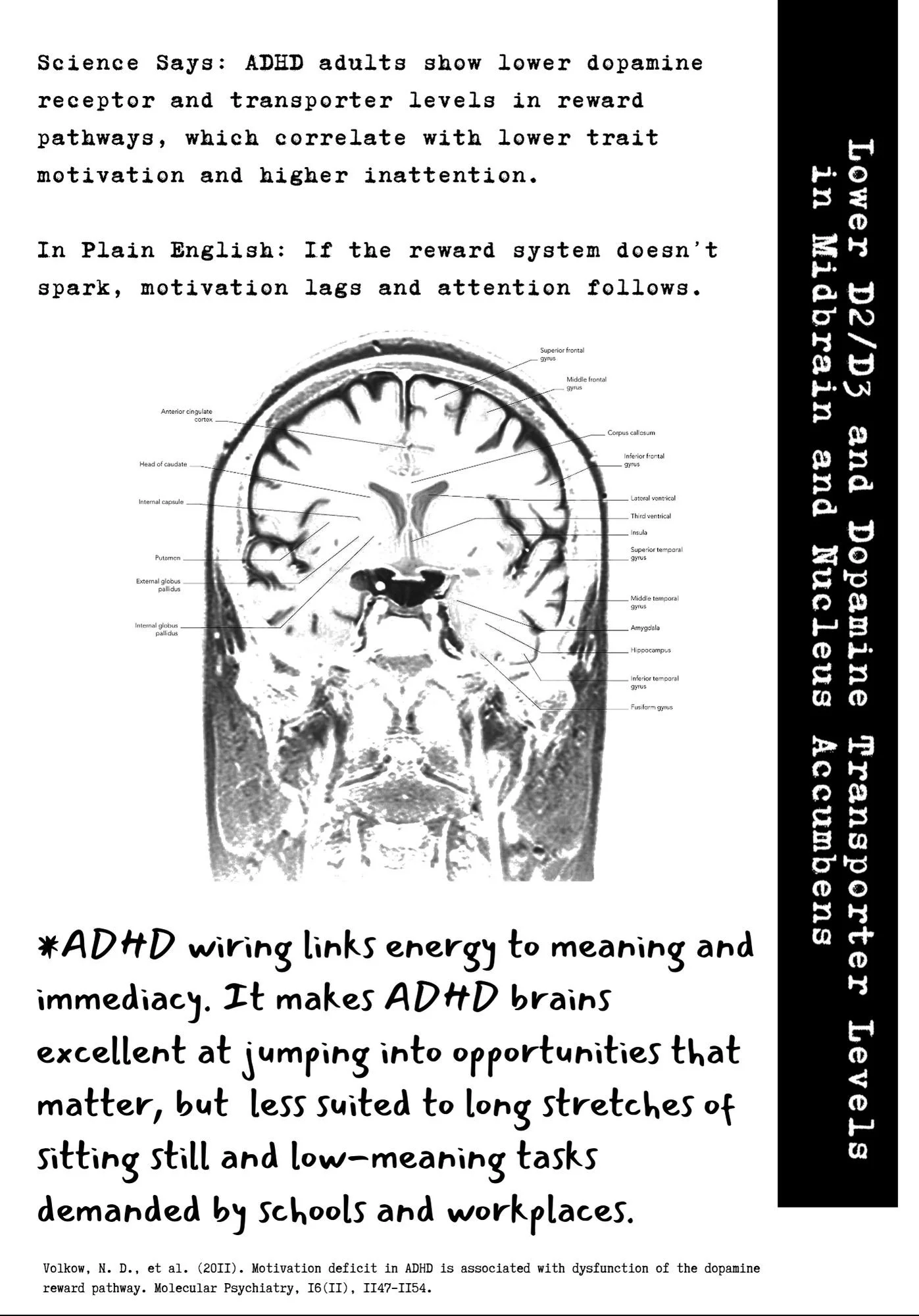

Lower D2/D3 and Dopamine Transporter Levels in Midbrain and Nucleus Accumbens

Volkow, N. D., et al. (2011). Motivation deficit in ADHD is associated with dysfunction of the dopamine reward pathway. Molecular Psychiatry, 16(11), 1147–1154.

Science Says: ADHD adults show lower dopamine receptor and transporter levels in reward pathways, which correlate with lower trait motivation and higher inattention.

In Plain English: If the reward system doesn’t spark, motivation lags and attention follows.

*ADHD wiring links energy to meaning and immediacy. It makes ADHD brains excellent at jumping into opportunities that matter, but less suited to long stretches of sitting still and low-meaning tasks demanded by schools and workplaces.

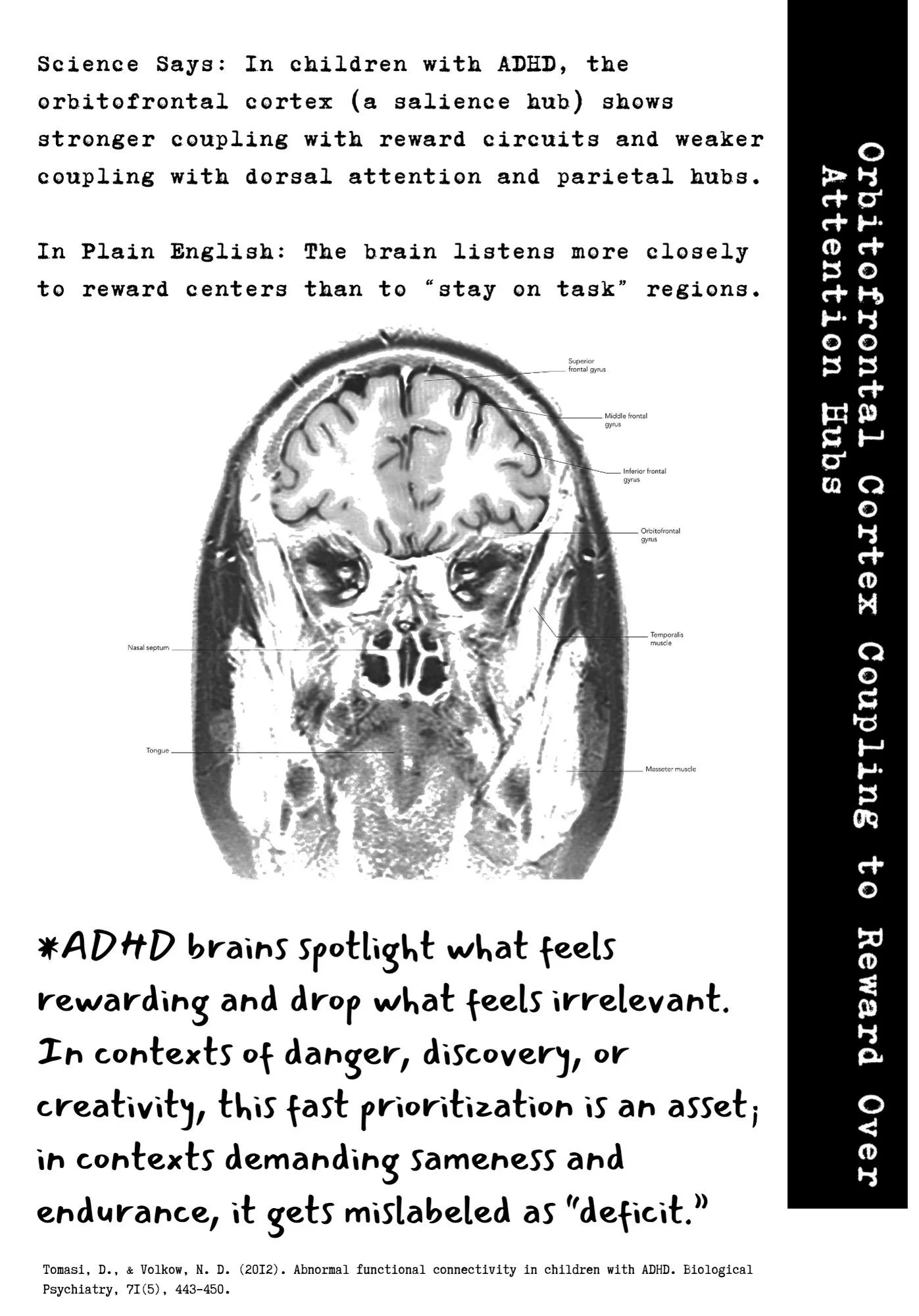

Orbitofrontal Cortex Coupling to Reward Over Attention Hubs

Tomasi, D., & Volkow, N. D. (2012). Abnormal functional connectivity in children with ADHD. Biological Psychiatry, 71(5), 443–450.

Science Says: In children with ADHD, the orbitofrontal cortex (a salience hub) shows stronger coupling with reward circuits and weaker coupling with dorsal attention and parietal hubs.

In Plain English: The brain listens more closely to reward centers than to “stay on task” regions.

*ADHD brains spotlight what feels rewarding and drop what feels irrelevant. In contexts of danger, discovery, or creativity, this fast prioritization is an asset; in contexts demanding sameness and endurance, it gets mislabeled as “deficit.”

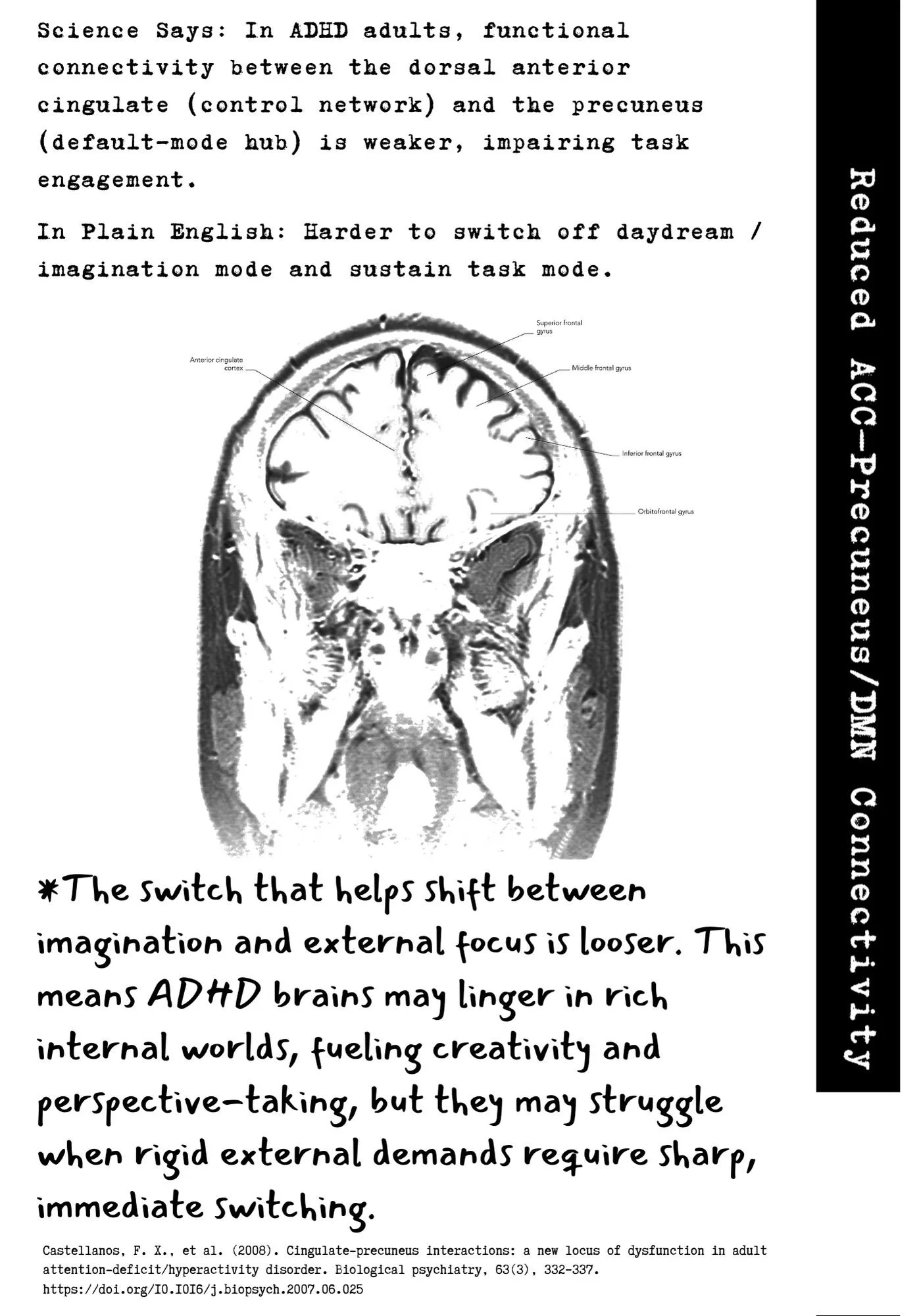

Reduced ACC–Precuneus/DMN Connectivity

Castellanos, F. X., et al. (2008). Cingulate-precuneus interactions: a new locus of dysfunction in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychiatry, 63(3), 332–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.025

Science Says: In ADHD adults, functional connectivity between the dorsal anterior cingulate (control network) and the precuneus (default-mode hub) is weaker, impairing task engagement.

In Plain English: Harder to switch off daydream / imagination mode and sustain task mode.

*The switch that helps shift between imagination and external focus is looser. This means ADHD brains may linger in rich internal worlds, fueling creativity and perspective-taking, but they may struggle when rigid external demands require sharp, immediate switching.

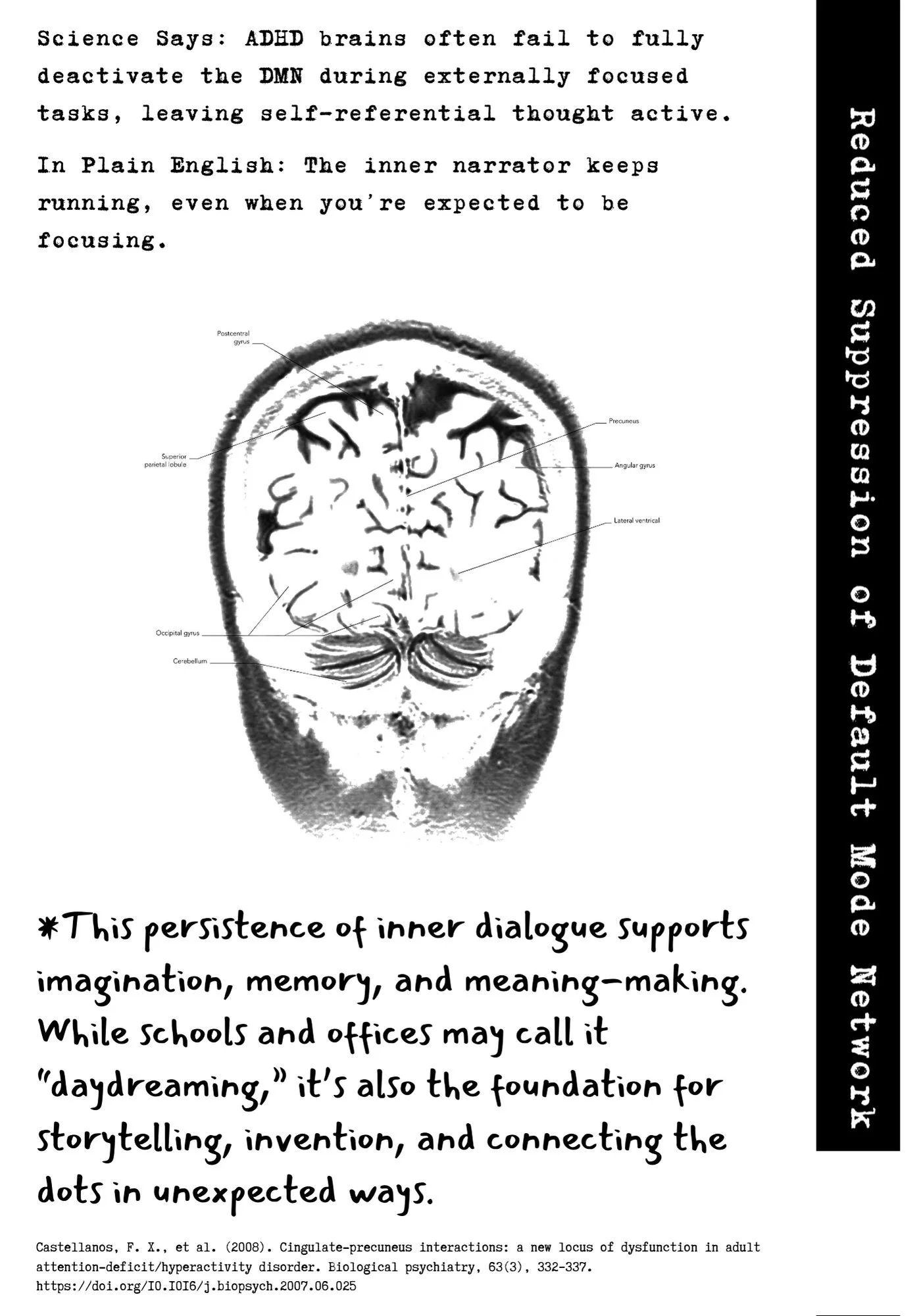

Reduced Suppression of Default Mode Network

Castellanos, F. X., et al. (2008). Cingulate-precuneus interactions: a new locus of dysfunction in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychiatry, 63(3), 332–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.025

Science Says: ADHD brains often fail to fully deactivate the DMN during externally focused tasks, leaving self-referential thought active.

In Plain English: The inner narrator keeps running, even when you’re expected to be focusing.

*This persistence of inner dialogue supports imagination, memory, and meaning-making. While schools and offices may call it “daydreaming,” it’s also the foundation for storytelling, invention, and connecting the dots in unexpected ways.

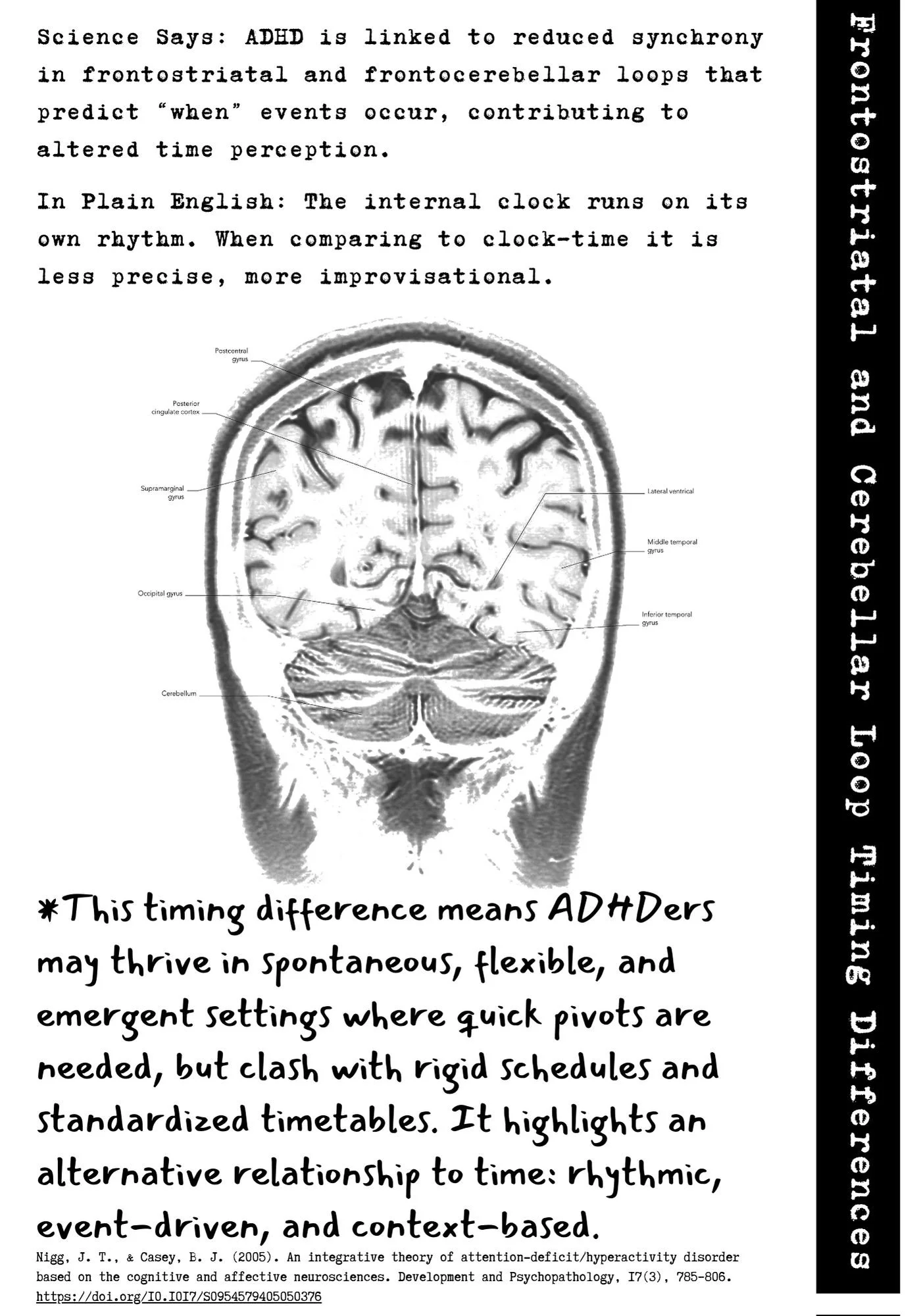

Frontostriatal and Cerebellar Loop Timing Differences

Nigg, J. T., & Casey, B. J. (2005). An integrative theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on the cognitive and affective neurosciences. Development and Psychopathology, 17(3), 785–806. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579405050376

Science Says: ADHD is linked to reduced synchrony in frontostriatal and frontocerebellar loops that predict “when” events occur, contributing to altered time perception.

In Plain English: The internal clock runs on its own rhythm. When comparing to clock-time it is less precise, more improvisational.

*This timing difference means ADHDers may thrive in spontaneous, flexible, and emergent settings where quick pivots are needed, but clash with rigid schedules and standardized timetables. It highlights an alternative relationship to time: rhythmic, event-driven, and context-based.

Reduced Behavioural Inhibition

Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65

Science Says: Barkley proposed that poor inhibition of behavior is a central feature of ADHD, affecting self-control and persistence on goal-directed tasks.

In Plain English: Thoughts and impulses show up fast and spill out before filters slow them down.

*ADHD brains are wired for responsiveness— words, ideas, and actions are more immediate. This can spark quick creativity, humour, adaptability, and boldness, though it collides with environments that prize restraint and delay over spontaneity.

Salience-Tuned Neurology

Across all these differences, one story keeps surfacing: ADHD is about salience — the brain’s system for deciding what is meaningful right now.

The thalamus lets more in, so more sights, sounds, and sensations compete for importance.

The dopamine system in the caudate and nucleus accumbens doesn’t always light up for routine tasks — it lights up when something feels meaningful, urgent, or rewarding.

The orbitofrontal cortex and salience hubs steer attention toward value rather than arbitrary demands.

The anterior cingulate and precuneus make switching between task and imagination less rigid — so internal stories often run alongside the outside world.

The cerebellum and timing loops mean time itself feels different: less linear, more event-based, more improvisational.

The frontal lobe’s inhibition is looser, so ideas and impulses arrive faster and spill out into the world.

Taken together, ADHD neurology is best understood as salience-tuned wiring: tuned toward novelty, immediacy, and emotional weight.

This wiring can clash with systems that reward sameness, stillness, delayed gratification, and monotony — which is why adhd is often labeled as disordered. But in contexts that value adaptability, creativity, and fast response, these differences are assets.

References

Heads up: Most of these are written through a pathologizing lens.

They describe ADHD in deficit language, frame neurodivergence as disorder, or measure us against conformity.

I cite them here not because I agree — but because these are the “official” texts we’re forced to decipher and reimagine. Science isn’t bad, but it is biased and judgmental. My work is about reading between the lines, pulling out what’s useful, and flipping the rest on its head.

Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65

Castellanos, F. X., Margulies, D. S., Kelly, C., Uddin, L. Q., Ghaffari, M., Kirsch, A., Shaw, D., Shehzad, Z., Di Martino, A., Biswal, B., Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., Rotrosen, J., Adler, L. A., & Milham, M. P. (2008).(2008). Cingulate-precuneus interactions: a new locus of dysfunction in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychiatry, 63(3), 332–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.025

Micoulaud-Franchi, J. A., Lopez, R., Cermolacce, M., Vaillant, F., Péri, P., Boyer, L., Richieri, R., Bioulac, S., Sagaspe, P., Philip, P., Vion-Dury, J., & Lancon, C. (2016). Sensory gating capacity and attentional function in adults with ADHD: A preliminary neurophysiological and neuropsychological study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(8), 646–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716629716

Nigg, J. T., & Casey, B. J. (2005). An integrative theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on the cognitive and affective neurosciences. Development and Psychopathology, 17(3), 785–806. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579405050376

Tomasi, D., & Volkow, N. D. (2012). Abnormal functional connectivity in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 71(5), 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.11.003

Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Kollins, S. H., Wigal, T. L., Newcorn, J. H., Telang, F., Fowler, J. S., Zhu, W., Logan, J., Ma, Y., Pradhan, K., Wong, C., Swanson, J. M., & Klein, N. (2011). Motivation deficit in ADHD is associated with dysfunction of the dopamine reward pathway. Molecular Psychiatry, 16(11), 1147–1154. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2010.97

Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Newcorn, J., Fowler, J. S., Telang, F., Solanto, M. V., Logan, J., Ma, Y., Schulz, K., Pradhan, K., Wong, C., & Swanson, J. M. (2007). Depressed dopamine activity in caudate and preliminary evidence of limbic involvement in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(8), 932–940. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.932

TL;DR

ADHD neurology is SALIENCE-TUNED: attention and energy organize around what feels meaningful, urgent, or alive now.

Differences in sensory gating, dopamine pathways, salience hubs, DMN switching, timing loops, and inhibition are VARIATIONS — not defects.

Struggles come from SYSTEM MISMATCH: sameness, stillness, and clock-time as moral law.

In the right terrain (novelty, purpose, flexibility), these traits can be ASSETS.